On Thursday Microsoft held a marketing live stream to show off the third-party titles releasing on the upcoming next console, Xbox X. These games are only possible because the hardware lets these developers follow their dreams

, the head of a marketing department says during the stream. His eyes are unable to focus on the camera, occasionally glancing below to his screen, likely distracted by the information systems keeping him connected to his family, friends, and work. From the walls of the speaker’s room being the backdrop to the conference to the distracted discomfort of his eyes, capitalism’s facade of normalcy falls to the creeping touches of the pandemic. Yet the game corporations continue to market, sell, and work.

How could life possibly go on without corporate game news streams?

Many have already been critical of corporate actions during this crisis and I don’t want to reiterate on those words. What I found more interesting coming from that conference was the fan reactions to the game announcements. I read a lot of people on discords and twitter saying that the conference signaled the continued state of games being boring. Franchises had returned, trailers cut to the same action set pieces showed, and the familiar, half-dead slogans from marketing heads. A parkour futuristic FPS here, a new Assassin’s Creed there, and all made possible because they have an iteration of the new plastic homogenized box.

While there wasn’t much from the show that caught my eye, I found some of the discussion around the games start to get a little gatekeepy from people whose opinions I respect most of the time. Specifically, this was in reference to the trailer for the new release in the Yakuza franchise. Yakuza: Like a Dragon is so amazing but if you want to play it you HAVE to play 0–6 to really understand all of the character interactions.

While it is important to be critical of how game companies are treating customers and workers during the pandemic I wonder, how do players uphold these corporate structures by sanctifying media canons?

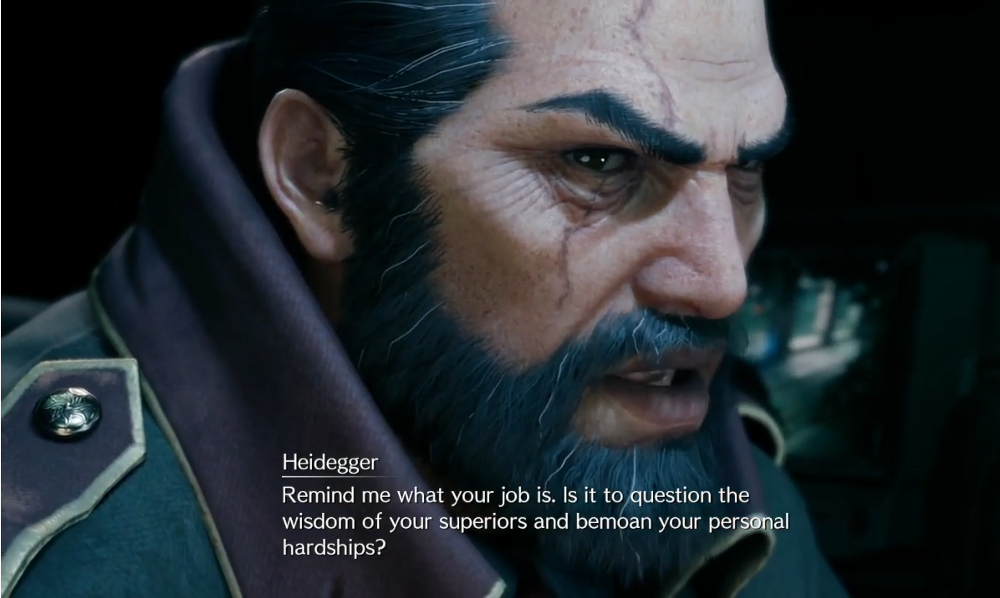

The sentiment is one that a lot of people have probably heard, depending on the communities and fandoms one intersects with. This is especially true as of late with the release of the Final Fantasy 7: Remake releasing to fans who have been drooling for decades. Final Fantasy 7: Remake has clearly been designed with the hopes that the player has played the original. If you haven’t played the original before, you are doing yourself a disservice.

O….K . These otherwise say, You disgraced pupil, you better educate yourself on years of arbitrary lore before you even think to touch something that was made for a fuckboy gamer like me.

If I wash the ashy taste in my mouth, perhaps the sentiment is more clear. This piece of media was an incredibly emotional experience for me that I cherish. I played some of these games at very memorable periods of my life and the arc of my life experience with them connecting to each other was what I would like others to experience as well.

When this statement is written this specific, the interaction becomes an act of sharing one’s personal experience, something intimate. The game loses its importance as an unbreakable thread that must be seen from the beginning to be unwound and becomes a person expressing their resonance with it instead. This, however, is not how these interactions are phrased, and instead the statements, such as the tweets aforementioned, becomes an argument in defense of canonical knowledge.

These canons are incredibly essential to this social phenomena, so I am going to go more in-depth with canons and talk about time travel. Please stick with me on this….

Due to the linear nature of existence, games are formed succeedingly within flow of time. If a sequel to a game is created, it can only be released after the creation of the initial game. This may seem incredibly obvious, but by recognizing this perception of time, it can be seen that products are designed to utilize this temporal movement.

First most, iterations build on the elements from the first title, and many times they return with fanfare. Art styles and gameplay elements are adjusted, characters return from the previous game’s conclusion, a long term plot is created. Remember when Garrus revealed himself as Arch Angel in Mass Effect 2? Yeah, that was hot. But it was so exciting because it built on the events of the previous game. In the original Mass Effect, the player follows the Vakarian freshly interrogating his own politics as he leaves law enforcement to join the protagonist’s pursuit of the Reapers and Saren. So to see him return in the second title with the reputation of being a high-profile mercenary vigilante is an exciting period of character development being revealed.

I will reiterate however, moments like this with Garrus are exciting, and it is not immoral in any way to enjoy these moments. But no one is incorrect for not having this exact, designed narrative experience.

Along with these iterated elements of the game, external elements utilize this temporality as well. Marketing research determines how the next iteration will appeal to an audience, fandoms are given care through community outreach and Easter eggs are revealed to garner interest.

When these elements all are put into a place, the market in this case, a canon is formed. The company that releases these titles recognizes a narrative that lines up when their games released. They don’t give away game timelines as pre-order bonuses without any recognition of their value. The canonical timeline of games are inherently valuable, because game products are designed for linear points in time. Fans recognize these timelines, and in many cases where the publishers of these games neglect to recognize their works, or move on to restart their franchises, fans still keep these timelines archived and maintained. This canon creates an insular set of knowledge for players to refer back to as a reward for staying loyal over the period of time iterations have been made.

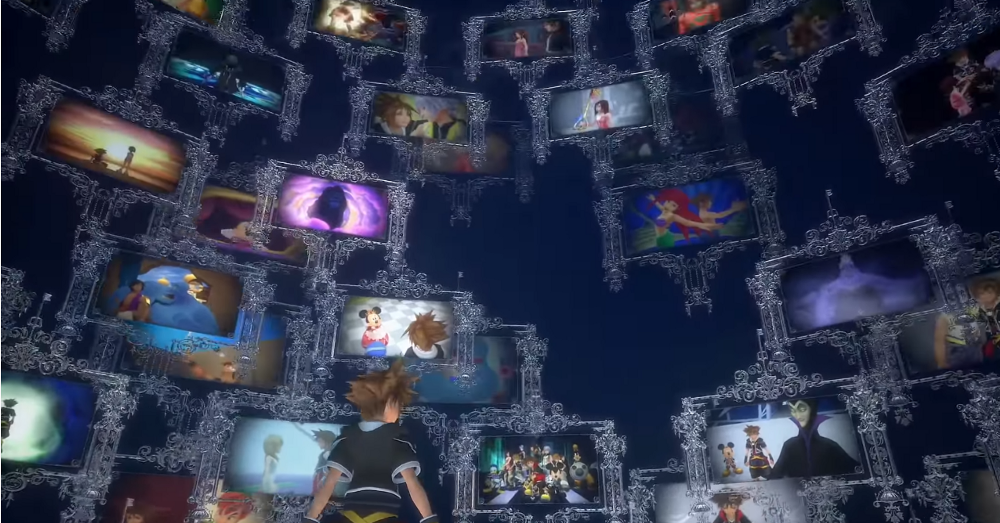

Kingdom Hearts, as an example, is perhaps one of the more prominent series to recognize the value of its canon within the player-base. When Kingdom Hearts III released, a lot of the fanbase came together to recognize the time they spent waiting for a relief to their continued 7 year-long perseverance waiting since the last title. Some of this stayed within the community, but there were also many jokes about how ridiculous the new game would be for someone new to the franchise. Imagine playing Kingdom Hearts 3 without playing the prequels

one tweet reads. These jokes are a way for other players to enjoy their perseverance and enjoyment together, but they also alienate anyone outside hoping to participate in their own way.

Very recently I was speaking with a friend about her new foray into the series, and when she mentioned her step from one game to the next I asked, Which game are you playing this after, Kingdom Hearts 2 or Chain of Memories?

. Although I did not intend for it to be, It was a investigative question. I was interested in whether or not she was playing in the canonical order that I had become familiar with. And before answering this question, I recognized in retrospect that it was one that likely held some pressure behind it. It wasn’t necessarily bad that I asked, I was sincerely curious to understand her experience. However, that same format of question has been historically twisted to alienate anyone who isn’t a man outside of game spaces. Just like the tweeted joke above, I was implying that there was an understood way that these games are played.

These insular canon knowledgebases and affective nostalgia are not anymore valuable than the experience of a new player beginning to play a game at any point in its realm of titles. Products form timelines as a consequence of their design around the perceived linearity of time. In contrast to the products though, audiences do not perceive media linearly. Therefore the timelines only have a limited amount of value compared to the experience of the audience.

When we experience a piece of media we are always connecting the past and present cultural contexts to what we are experiencing. Our brains recognize familiar forms, gestures, materials, sounds and more that allow us to navigate through our lives. So when these same signs appear in media, they evoke responses. These responses may be ones that we understand that come in the form of language, but other times they may come in the form of emotions or another unclear response.

Many academics use semiotics to explain this phenomenon. This idea states that there is the form something is signaled, for example the way I say bottle, and then there is a separate understanding of that form as a concept. So if I say bottle, that is the sign, and you understand that to mean, perhaps, the bottle on your desk, that is the signified. This is the idea of semiotics, but specifically with media I’d like to argue that there is a form of perceptual time travel that occurs when we experience media.

To keep things directed and staying with games, when we play games we are always evoking responses that came from previous points in our lives. There are concepts of rules and goals that a player understands they need to figure out when they decide to play. This is why the first question asked many times with games is, what do I do?

. With ideas, we have gone through life understanding what objects mean to the world, so when they appear in media those understandings are brought to the forefront.

When we play games we experience a series of these concepts delivered to through the game design itself. It may be a little wild to propose this, but maybe I can argue here that games are time machines and by evoking past experiences from our lives we are the time travelers.

By time travel I don’t mean that one is literally shifted to a time in the past, although for some with certain traumatic experiences this may be the case. Instead, I am arguing that we are never exclusively moving forward in time. If we only live in the world as we perceive it, then we only have memories of our perceptions, insular to our brain. Therefore, when we have certain concepts evoked, our brain moves through those memories in the brain. When I see a destroyed house in Final Fantasy 7: Remaster, I think back to all of my understandings of destroyed houses in my life. Those houses make me angry thinking of people who had their houses destroyed by landlords looking for money in 1970’s Bushwick, and the ongoing violence caused by the US military in the middle east. The past and the present perceptions become entangled in order to make meaning.

However, this media based time travel is never a limitless one. The video game as a time travel vessel is commodified, built by the labor of workers commonly exploited and fostering a homogenized patriarchal lens that defends and erases ableism, colonialism, homophobia, imperialism, racism, and transphobia. That does not mean there are not many creators fighting against that, but this has been a problem with the culture for decades as many know.

When this vessel is recognized, explicit values emerge. Players understand that there is conditions and intentions that are held within the vessel. When the vessel is not recognized, implicit ideologies are educated and internalized. Neither recognizing or not has an inherent morality. People can recognize values of hate and align themselves with them. However, at least by recognizing the vessel there is a choice we make in that alignment. By allowing ourselves to enjoy the vessel’s path of travel without understanding what is happening, we allow ideologies to imprint upon us. This can create fanaticism at the least, full blown imperial-nationalism at the most.

It is from this lack of vessel recognition and upholding of insular corporate timelines that the arguments of holistic experiences are formed. To go back to the rephrasing I wrote earlier, players have emotional connections to the experience of media consumed time travel. They touch certain moments of life, and resonate with understandings of the world. However, it is the fanaticism and consecration of these canons that only makes for a space in games meant for the audience that the corporation intends. The media was designed to be consumed this way, and you must follow the rules to enjoy it. Those loyal to the corporations throw their bodies onto the walls of defense in order to maintain order.

This is not a radical sentiment, but a hopeful one. In Kimimi’s writing on SNK Gals Fighters, she writes,

I like games. That’s all there is to it. I want to be normal within my preferred hobby, to be allowed to exist within that space simply by deciding I want to be there. Not an exception (or exceptional). Not apart. Not having to justify myself to random guys who think a tatty copy of Super Mario Bros 3 makes them the oracle of retro gaming.

Must one have prior experience with a sphere media in order to participate in an experience they are interested in? Perhaps the question is not one of how one should play, but whether one holds the corporation over the individual.

Waverly's blog

Waverly's blog